One late April day, I found myself moving firewood between two sheds in northern Minnesota. It was a point in the spring when the sun should be just starting to shine warmly, or the rain should be falling upon flowers just about to blossom. I was caught in a mid-day blizzard, the immediate surroundings completely wiped away by the winds and snow. I knew that around me were miles of conifer trees, wetlands, and small lakes that had been scratched from the Earth 10,000 years ago by glacial retreat. From the rocky glacial cliff the sheds sat upon, I could barely see Pickett’s Lake below. It was in this setting that I, a young volunteer staying at a familiar homestead, found myself moving wood that had been drying for two years one step closer to its final destination, the cabin woodstove. Next winter it would be the main heat source for the aged and wise arctic explorer I was volunteering for.

I expected nothing from this action for myself, except to help out a man I consider a mentor and a hero. He was away somewhere, speaking at a university or on a dog sled expedition into the Canadian Barrens, taking data along the way that would help scientists understand how the world is shifting and changing. I was alone here, familiarizing myself with the etches and bug paths laid into old beams of wood, protecting the potential of future heat from the elements I could not escape. Moving firewood from one shed to the next. Today, that would be my contribution. That evening, I would go to another tiny little cabin where I was staying, and burn some firewood that someone had moved for me, and eat something that someone had grown or hunted, and then kept cool in the root cellar just across the way. The root cellar where the summer before I had taken breaks to drink juice, escaping the hot summer sun in coolness which had been harvested that February from the lake, in the form of blocks of ice, cut and dragged to this place in celebration for the hot months to come. This was a place of cycles, and harvesting energy from the present to save it for the near future.

Our society does this work all the time, except on a much greater time scale. We harvest energy from millions or even billions of years ago in the form of fossil fuels or rare earth minerals. These are the remains of ancient algae or even more ancient stars, turned into energy for the present at our leisure. This transformation of ancient energy allows me to move firewood from shed to shed for my mentor in the first place, for it was that ancient energy pumped into my car which enabled me to travel the 200 miles to get here in only four hours. I drove here from my college dorm to spend a week seeking a life I so desperately wanted, one of existing simply in the day-to-day tasks of life off the grid.

The path to a socially, economically, and ecologically just culture lies in simplifying life and its expectations. We expect so much in our desires, as we seek a world in which every individual can have a smartphone, a two-story house all to ourselves, and can travel the world as much as they’d like. This approach to life, the consumerist philosophy of self-enrichment, is starving our society, and the ecologies which surround us.

The American Dream in its modern, neoliberal form depends on an ever increasing “quality of life”. More economic activity and more money exchanging hands becomes essential at every level, and an enterprise which is not constant increasing its productivity is bound to closure. In modern terms this means; increasing automation and the ease of everyday tasks, making everything “convenient”, and consuming more and more material goods. A smartphone increases ease of communication, a personal car increases ease and independence of transportation. This ease denotes a perceived increase in the complexity of technology and actions. This ever-increasing complexity has become the standard upon which our quality-of-life rests. The American populace embodies ever more complex desires and standards, with the assumption that increase in complexity is linear and perpetual. Yet as every innovation adds a thread to our web of complexity, the energy which is returned on energy invested decreases, as it takes more energy investment to yield a lower increase in complexity. Like a spider’s web which is weighed down by too many threads, our own innovations are becoming a weight the world cannot bear.

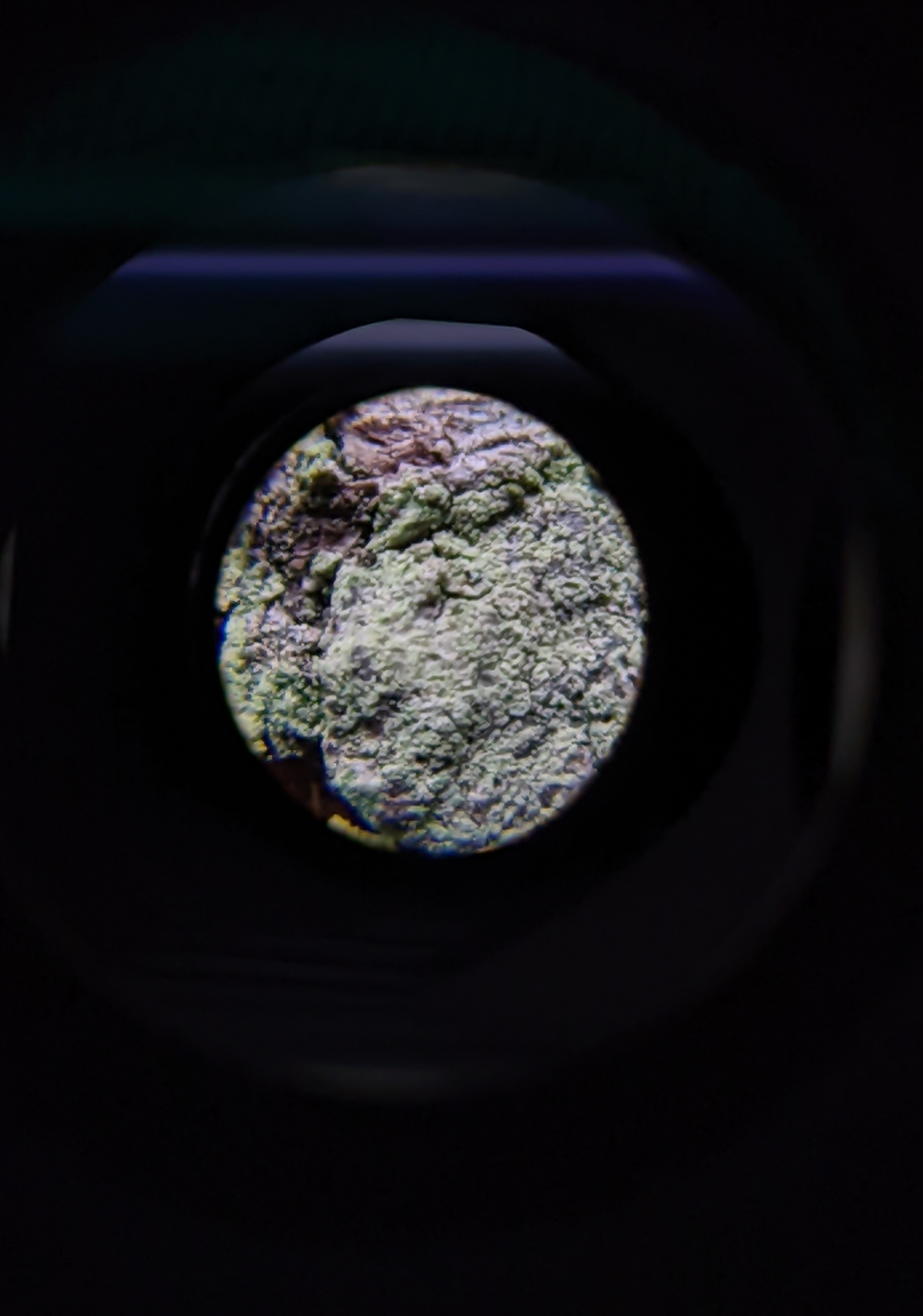

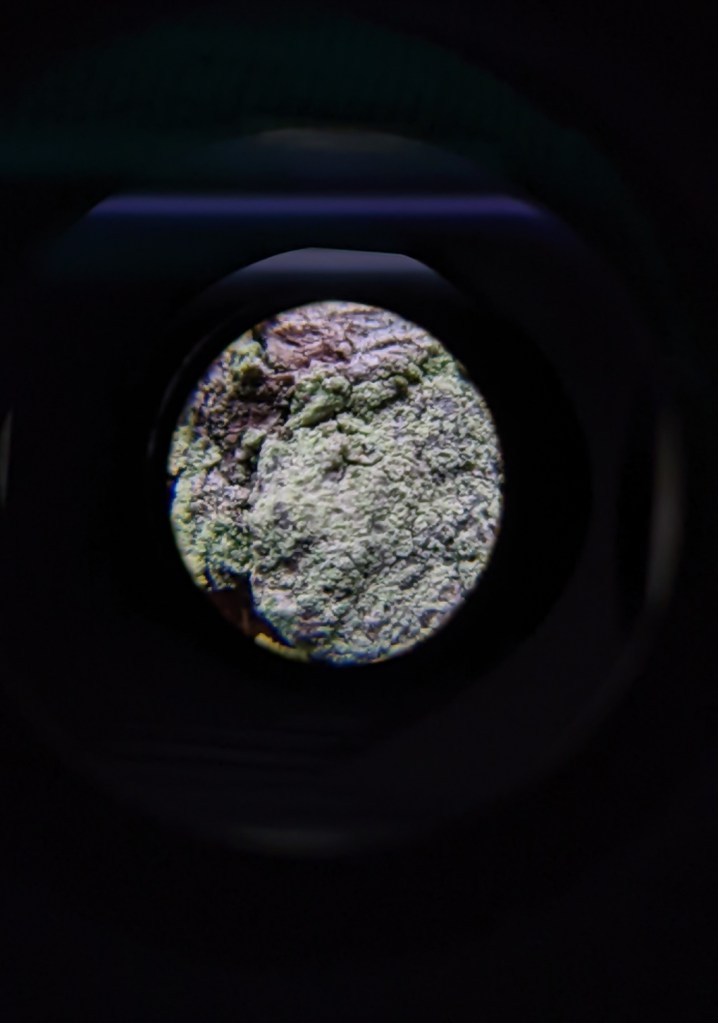

At the homestead beside Pickett’s Lake, I had to use my technology carefully in order to balance my energy consumption and return. I drove the truck sparingly to haul lumber from the warehouse to the mill, for the nearest gas station was an hour away in town, and I didn’t want to be the cause of a two-hour diversion just for gas and some snacks. I spent a couple of those spring days, after the storm had passed, scanning old beams of wood with a metal detector, searching for and removing any nails so the beams could be milled and reused, rather than having to find and cut another tree which had been storing energy for over one hundred years. My tasks at the homestead were all focused on using some energy, in this case my physical effort, in order to conserve the total energy of the ecosystem around me, an ecosystem which included the human elements of the homestead. At the end of the day I would climb to the top of the of what we interns and volunteers called ‘The Castle’, rising at the top of a small hill five stories above the coniferous expanse of the Northwoods. This was the only place on the homestead you could get a phone signal. The solar panels below had given my phone a couple hours charge, and I used it to listen to MPR Classical up here at the tops of the trees. I would write one text message to my mother, then use the remaining daylight to read my book. Here at the homestead, I had to use my energy to maximize my joy.

Energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) may be understood as a ratio between the amount of energy expended to create a given good or service and the amount of energy that good or service returns to the user. Take fossil fuel extraction- as a resource becomes rarer, it takes more energy to extract a fuel source which yields the same amount of energy as more easily accessible sources, thus diminishing EROEI. More energy is expended in order to extract the same amount of potential energy. In our case ‘energy’ may be understood as work derived from resources, or as the joy or pleasure a good or service brings to our lives. In a modern context, it is taking ever so slightly more energy to extract the resources needed to create a smartphone each year, due to increase in the rarity of those resources. At the same time each new smartphone model produces a smaller amount of new energy than the previous new model did. The 10th generation of a smartphone does not change the way you interact with the world the same way the very first model did. In this way each innovation returns a smaller amount of new, vibrant energy than the previous innovation, as the ratio of EROEI steadily levels off. The curve of complexity is not linear, but rather is an inverse exponential curve which may increase quickly in the beginning of an innovation, but which soon levels off until a new, more energy intense innovation increases the curve yet again.

As stated earlier, the current iteration of the American Dream depends upon a steadily increasing level of complexity, which depends upon a consistent or increasing EROEI. It is increasingly acknowledged that this materialistic narrative is unsustainable and corrupt, and that some form of transition is required. Progressive movements ranging from Extinction Rebellion to Occupy to Black Lives Matter have sought to reclaim and reframe this bootstrap complexity narrative, creating a diversity of visions of future ‘American Dreams’. The long-term goal of these movements was to have their version of the future American narrative to be accepted by the general public.

Modern economically focused progressive movements have tended to focus on the idea of redistribution. Redistribution would use resources obtained from the upper classes in order to provide a more equitable economic situation for everyone. Over time this approach may level economic differences between classes. The goal of these movements has consistently been to raise the quality of life of the masses to equal that of the contemporary vision of the American dream, and thus increasing the standard level of complexity to be expected for a normal member of society. In this vision, the base assumption might be that, after basic needs are met, every member of society should have access to the latest personal technology. A smart fridge in every home.

While this an admirable goal, the Earth’s ecological capacity does not allow for each human to possess each latest model. We have long surpassed point in which the Earth cannot support raising the global quality of life to American standards. There are simply not enough accessible rare earth metals for each person to have the latest smartphone technology, or enough fossil fuels for each person to have a personal car, and AI stands ready to make this problem worse with the need for immense processing power. The carrying capacity of the Earth already exists in a state of overshoot, as we see daily examples all around us of dwindling resources and long-lasting pollution. In this overshoot state, civilization is kept in a relatively stable state by massive energy investment. The tar sands oil fields are a prime example of the energy required to stabilize our civilization. Each gallon of tar sands crude oil takes a higher energy investment to extract and process than previous oil sources, while the energy return remains approximately the same. Thus, more energy is expended to yield the same amount of energy return. A higher quality of life characterized by unsustainable energy input.

However, information technology and personal transportation are great enablers of social movements. They enable such social ties across regions that previous technologies couldn’t maintain, and make it much harder for the state to repress social movements it deems subversive or chaotic. The question before us is more complex than simply abandoning or embracing complexity, but instead evolves into a question of how to live within ecological means while enabling the continuation of social movements without repression. The answer, as far as there is one answer, lies in the simplification of lifeways, in order to maintain the continuation of technology which truly adds to the human experience.

The ideal of simplicity has long been woven into the American narrative. Narratives of Walden Pond and homestead culture, while deeply entwined with narratives of colonialism and American Empire, can a base point of understanding, commonly known among the average American mind. Most Americans can create a picture in their minds of this ideal, the cabin in the woods, the simplicity of a day spent tending the beanfield overlooking a lake. If movements are willing to acknowledge the flaws of the pioneer and back to the land narratives while learning from their lifeways, these narratives can serve as a basepoint from which a common understanding can be built. Just as American Empire has the stories of the bootstrap narrative and exceptionalism, so to must the movements of The Great Turning develop a relatable, diverse narrative to espouse a better life.

During my time at the homestead, I would spent my days weeding the raspberry patch, pulling a third of an acre of horsetail away from newly planted raspberries. This probably took more energy from me than would ever be returned in the form of raspberries, but this act fed my soul well enough. I would then climb into a canoe and paddle the lake for a time, before hopping into the Lake, enjoying the sauna, and then spending time in whichever little cabin I was staying in that week. This routine became an idealized story I would tell myself over and over again for years, as the kind of story I most wished to live.

I, like some peers of our generation, have always dreamed of the ideal of the cabin in the woods, the simple, regenerative life. I’ve dreamed of the life that my mentor and many others like him lived in the 20th century. Twenty acres, and a cabin in the woods built by hand. A place to create a home, and an ecology to regenerate. Yet in looking to foster that life for myself, I found a certain irresponsibility in leaving my community behind, and an irresponsibility of taking twenty acres of land for myself. My peers were right, when they asked how I could leave behind the human spaces of the world when people like us were so desperately needed to change society. We cannot step back from our human community, yet we must acknowledge the complex energy imbalance of neoliberal society cannot be maintained. The energy investment is simply too high to maintain a similar level of energy return. Thus, simplicity and sharing of space and resources becomes the crux of our narrative. The action of community is the essence of simple living.

A community oriented towards simplicity instead of individualistic complexity requires strong institutions in order to meet its needs. It needs community members to be conscious of the resources they possess, and which their neighbor is in need of. It needs strong systems to share resources amongst its people, and commons spaces to create mutual bonds. And these institutions already exist, in the age old example of the library. The sharing of knowledge through collective ownership of books has for millennia been an indispensable part of human community. This model of collective ownership of knowledge can and must be expanded to include skills, tools, information technology, transportation, and any other part of our lives possible.

This collective sharing of resources can be seen today in the proliferation of Maker Spaces. These are collective organizations in which members share tools and space in exchange for a monthly fee or a few hours labor. For a cost which may be physical or monetary, one has access to a workshop they could not otherwise afford. Here a woodworker or a metal artist shares their resources for the benefit of the whole community, and in turn receives a space in which to do their work, in community among others with similar skills and different backgrounds.

As a model, Maker Spaces point towards community-oriented approach, in which resource intensive tools are shared, instead of individualistically consumed. As rare earth metals become more energy intensive to dig up, this model can be used to continue our access to social media and information in a collective manner rather than as an individualistic pursuit. If we act early enough, our choice is not between continued access to technology or ecological health, but rather in how we collectively access technology. If we collectively own smartphones, rather than individually, we can continue our relationship with technology while cultivating a relationship with ecology and ourselves.

Moving firewood or sharing tools and workspaces is part of a practice in simplicity, cultivating our quality of life and a deeper understanding of ourselves in the context of community. Through sharing energy intensive processes that define American lifeways, such as tools, transportation, information, we deepen our own human experience. We share tasks with the clear intention of limiting the complexity that defines the consumerism our lives. Simplicity is the point of greatest energy return which can be sustained over generations and matches the quality of life we desire. In order to embrace this simplicity, we must tell a new story, a different story, in order to fit our lives in a new, less fragile mold.

There are many steps we may take to foster simplicity in our lives. In the most concrete sense, we must create the spaces where simplicity thrives. We can build tiny houses, to live within a smaller footprint. We can create maker spaces, and add technology like smart phones and tablets to libraries, to render owning our own individual technological tools less necessary, or even cumbersome. Collective ownership of resource heavy tools, anything from smartphones to table saws, will enhance the social capital of our community, and help make these tools accessible to a greater diversity of people. These spaces lower our footprint on the planet, and enhance our connection with one another.

More deeply, we must participate in the movement of unlearning and remolding our stories, and our expectations of ourselves. These stories already exist, and we must simply open our ears to listen. The narratives of the Great Turning, permaculture, and social justice are already stories which are told in our culture. By expounding upon and living as best as we can within these stories, they may begin to become the expectations of our society, replacing the consumeristic dream of today. Moving firewood from shed to shed has become part of my story of social justice, as I strive to do good as an action rather than as a concept. We must actively participate in whatever a simpler world means to each of us individually. Each of us can be a model, showing to our peers that simplicity, without giving up the advances of our society, is possible. Showing that by living simply, we may finally be able to live in the socially just world we have strived so long for.